As September approaches and the courts get set to grind back into action, Galway Daily takes a hard look at the Irish penal system.

A middle-aged man serves no jail time for assaulting a child.

A burglar committed several thefts after receiving a non-custodial sentence last year.

A threatening, abusive neighbour will be able to stay at home pending a behaviour review.

These are some of the court stories Galway Daily reported just this year – and at first glance they seem shocking.

But to find out why our courts often seem too lenient with the most dangerous members of society, we have to examine what we know about crime and criminal behaviour.

Why do we have prisons?

Prisons are for retribution, deterrence, prevention, and rehabilitation.

Most people think of prisons as a deterrent.

They prevent people from committing crimes out of fear of the consequences, or they can also separate criminals from society to stop them from committing more crimes.

But the most complex function of a prison is to rehabilitate criminals – to somehow get them to live as contributing members of society after the experience.

This could be done by making prisons such horrible places that criminals never want to go back, which works in theory but not in practice (not to mention the human rights violations).

Or it can be done with support systems for criminals to help lift them out of the situation that bred the bad behaviour in the first place.

Many European nations – including Ireland – are opting for the latter route.

Isn’t it simpler to just lock them all up and throw away the key?

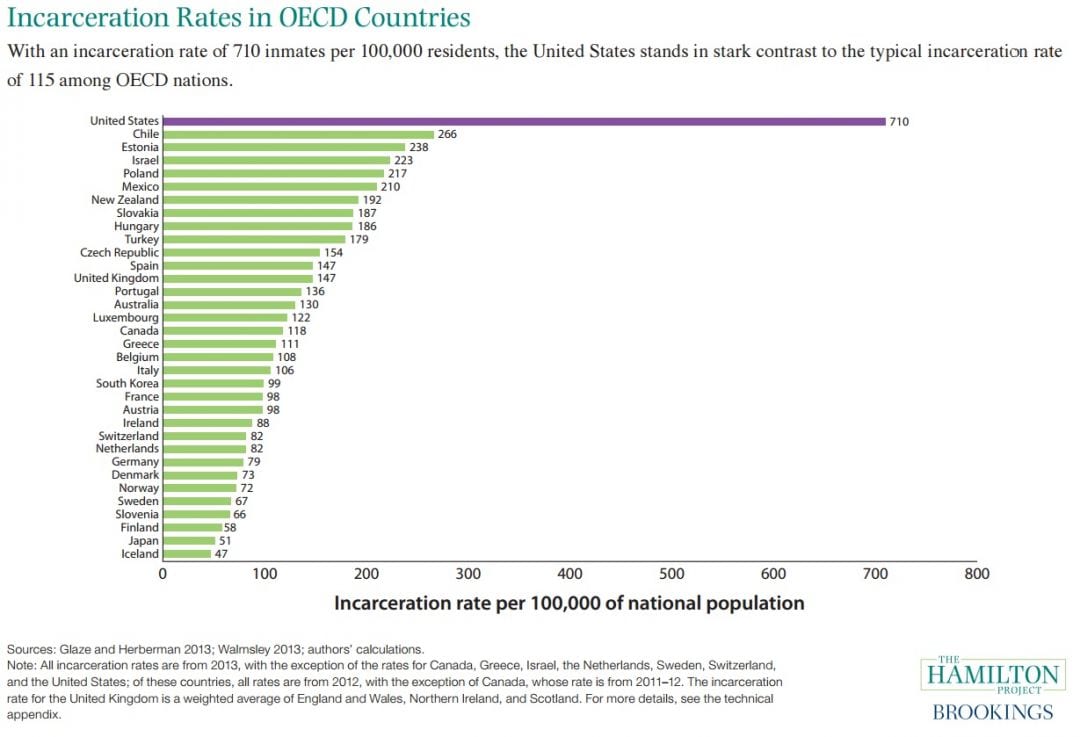

That’s what the US is doing.

Since their ‘tough on crime’ policies in the late 70s and 80s, their incarceration rate (the number of prisoners compared to the number of people generally) skyrocketed to the highest in the world.

Sentences there are also longer.

And take a look how it’s working out for the Americans.

Not only are their prisons exploding with people, but their recidivism (reoffending) rates are as high as 68% re-offending within three years of release and 83% within nine years.

Although some attribute recent low crime rates to the spiking incarceration, experts believe it had a minor and diminishing effect (see a detailed data-driven analysis here).

The ‘tough on crime’ approach simply does not work.

In fact, in the article linked above – subtly titled ‘Prisons Do Not Reduce Recidivism’ – the researchers find evidence that imprisonment can actually have a criminogenic effect, meaning it becomes a social experience that may deepen an inmate’s involvement in crime.

So we have to try something else.

Why taxpayers should support criminals

Although this approach – giving resources to those who arguably least deserve it – may seem counterintuitive and costly, it appears to work.

Remember the Netherlands, where 90% of sentences are one year or less?

It’s really working for them – many of their now-defunct prisons are being transformed into multiple-use spaces.

Not only are their crime rates low and still falling, but their recidivism rates are following the same pattern.

Plus Dutch citizens feel safer – a 2017 OECD report revealed that assaults fell to 0.6% and people felt more safe when walking alone at night.

Understanding the economic and social factors that drive people to crime allows us to tackle its root causes.

In fact, psychologists think that one of the main reasons prisons don’t fully work as a deterrent is that most crimes are committed by people who differ in important ways from the general population.

Criminals tend to be disordered, with rampant mental health and substance abuse problems and high incidences of cognitive and developmental impairments.

Socio-economic factors also play a role, with most criminals coming from backgrounds of deprivation and abuse.

These factors affect who falls into crime in the first place – but also makes it very difficult for them to break the cycle and pull themselves free.

What about Ireland?

Ireland’s policies follow the European trend of focusing on rehabilitation over retribution.

Here, prison is viewed – at least officially – as a ‘last resort’ penalty for criminal behaviour.

Yet prisons in Ireland are still overcrowded, with conditions that the UN Committee on Human Rights called ‘inhumane’.

And a 2013 study on recidivism in Ireland found that 62.3% of criminals re-offended within three years of their release.

This is comparable to the US rate of 68% and far higher than the 27.5% recidivism (within two years) reported by the Netherlands.

Meanwhile, the crime rate in Ireland is surging.

So why is this not working for us?

A 2012 paper on the Irish prison system by the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice notes that:

“The system is being asked to deal with the consequences of inadequate or failed policies across a whole range of areas, from income distribution to education and training services; from mental health care to family support services…

“…there [is] a significant gap between the espoused official values and overarching policy statements regarding the development of the Irish prison system, and the

decisions and actions that have been taken over recent decades.”

In short, it seems that the lenient sentencing works in the Netherlands because they have the support systems to back it up.

A reform of Irish prisons to better support those in their care could make a huge difference.

As we get ready for another year of court stories, we should all keep in mind that sometimes a little compassion goes a long way.